Dr Stephen Wright worked as a consultant physician at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (HTD), one of the hospitals that comprise University College London NHS Foundation Trust, for almost 30 years. During that period he spent three years in Saudi Arabia at the Medical School in Riyadh and had previously worked in Nigeria and Nepal. He has been involved as an expert witness over a wide range of tropical and imported diseases: melioidosis, schistosomiasis, brucellosis, gastrointestinal infections, Lyme disease and malaria. With malaria is probably the most important tropical infection that he has provided opinions about acting for the Claimant and the Defendant in different cases, Stephen discusses more about tropical diseases and the law.

At what point would you recommend clients to take legal action?

When there has been an adverse outcome for a patient it is essential that a doctor should provide an adequate explanation as to the causation of this outcome. Increasingly practitioners are advised to offer an apology where that is due and to discuss events with the patient or their family. In the context of infections it is usually delay in appreciation of the severity of a patient’s condition or in referral that leads to circumstances in which a patient or their family should seek recompense through legal action.

As with so many problems that arise in practice, doctors ought to listen to the patient, consider what they present with and communicate what you intend to do and why. Problems arise in so many situations when doctor and patient are not on the same wavelength. Doctors should always seek advice when they need it.

How has your international experience enhanced your medical ability, especially in tropical medicine?

It is valuable for practitioners in many fields of medicine to have spent time working in the tropics. In the last year I heard an inspiring lecture by an orthopaedic surgeon who had worked at hospitals in tropical Africa. I, like him, have gained valuable experience from working in West Africa, Asia and the Middle East, which has given me insights into late presentations of diseases that are described in the books but not often seen in the UK.

While I do not undertake clinical duties there, I have been involved in teaching the postgraduate East African Diploma in Tropical Medicine & Hygiene course (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine) for over six years in Uganda. I have worked as a tutor on field trips. This has been of great value to me in giving me first hand experience of East African sleeping sickness and in more recent years the impact of schistosomiasis (bilharzia). This year I will be involved in developing a new field trip module on infections acquired from animals, zoonoses.

How has the field of tropical medicine progressed over the years? Due to more people actively travelling abroad, and medical advancements, do you think this progression has changed legal cases taken to court?

The scope for diagnosis of imported infectious diseases has increased as the range of diseases recognised in the tropics has increased. Fortunately, deaths due to falciparum malaria in the tropics, particularly Tropical Africa, have declined over the past two decades as progress has been made in prevention of infections with impregnated bed nets and the introduction of new antimalarial drugs, particularly the artemesinins. Well tolerated, malaria prevention medications are available and doctors, particularly in general practice, may be called upon to advise on what to take. Providing travel health advice requires more than just looking up recommended vaccines and prescribing an anti-malarial.

During holiday travel to exotic parts of the world a normally cautious traveller may cast aside their usual patterns of behaviour. Time taken in giving travel advice is frequently not remunerated but is immensely important for the traveller. I stress again what I said earlier: if a patient says, “Could I have malaria doctor?” err on the side of doing an urgent blood test for malaria or arranging urgent referral for hospital assessment, rather than not.

Aside from objectivity, what do you think makes a good Expert Witness?

When approached about a case I ask myself if I can honestly add value by giving an opinion. Knowing my limitations is something that has governed my responses to requests. A good expert witness would never take on a case just because they are offered it. They should know the areas in which they can claim expertise.

When I was asked to provide a list of areas in which I consider myself “expert” in, I listed eight or 10 topics/conditions/infections in which I believed that I could provide an expert opinion. Over my years of NHS consultant practice I have seen a wide range of patients with a wide range of imported infections as well as ubiquitous infections that could be acquired anywhere. I would not consider myself to be expert in all of them.

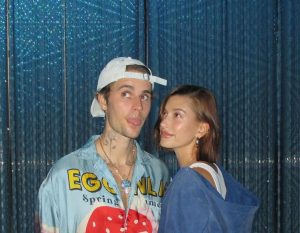

Dr Stephen Wright

Consultant

stephenwright1@doctors.org.uk

Dr Stephen Wright worked as a consultant physician at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (HTD), one of the hospitals that comprise University College London NHS Foundation Trust, for almost 30 years. His particular areas of interest have been gastrointestinal infections including giardiasis and amoebiasis. His time in Riyadh gave him experience of brucellosis and he has also had much experience of schistosomiasis, bilharzia. During his years at the HTD, he managed a wide range of imported infection arising from travel and overseas residence. In the last 20 years, he has gained experience of Lyme disease and have a very active interest in this condition. While he retired from NHS practice in 2010, he continues in private practice seeing patients at King Edward VII Hospital, Sister Agnes, London W1G 6AA.