The Value Gap: what is it?

Digital technology has revolutionised the music and entertainment industries in many ways, not least in the way in which music is distributed. The old “analogue” distribution paradigm has been turned on its head, especially in relation to physical products, and technological advance continues to create new and exciting opportunities, not only for getting the product to the consumer but also for establishing new relationships with consumers. This also presents a number of real challenges to the financial ecosystem that must underpin this growth.

The main challenge is the difference between the revenues effectively received by rights holders from the exploitation of their copyrights by content-sharing platforms, such as YouTube and Facebook, and the value that those platforms receive from exploiting such content. This is commonly referred to as the “Value Gap”.

Many rights holders have been vocal in their disapproval of the amount of royalties they receive and, in certain cases, have withdrawn their repertoire (if only on a temporary basis in some cases).

The sense of “injustice” that creators feel around the “Value Gap” issue is exacerbated by the growth of digital revenues enjoyed by those commercialising the music. According to the recently published Global Music Report 2019 from the International Federation of Phonographic Industries (IFPI), representing record labels and artists, paid streaming accounted for 37% of the total global recorded music revenue in 2018.

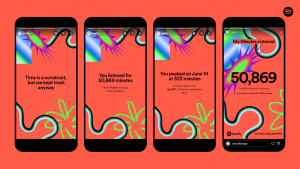

However, the “Value Gap” isn’t just created as a consequence of non-payment of royalties. Even where deals are being reached voluntarily between rights holders and the relevant digital players, those deals may still not satisfy the requirement for value or a “fair share” of the value created by the products using rights holders’ IPR. Take Spotify – a driving force for streaming – as an example. Many rights holders have been vocal in their disapproval of the amount of royalties they receive and, in certain cases, have withdrawn their repertoire (if only on a temporary basis in some cases). Nevertheless, Spotify has been reported to spend roughly 80% of its revenues in rights payments. This is clearly an unhealthy situation for both rights holders and Spotify. It’s also been variously reported that the difference between royalties received by ad-based content-sharing platforms and services like YouTube, and subscription-based services such as Spotify, is between five and twelve times. This comparison should be treated with some caution though as, whilst there might be some commonality in the experience the user enjoys, there are also differences between the services. This also illustrates the degree of disparity that characterises the “Value Gap”.

Furthermore, although the legislative change in Europe has been hailed as a major breakthrough, only time will tell the extent to which it closes the Value Gap.

How can the Value Gap be closed?

Traditionally, the origin of the Value Gap is rooted in the “Safe Harbour” provisions that exist in legislation in the USA and Europe. This legislation establishes exemptions for content intermediaries from direct and indirect responsibility for copyright infringing content in user uploads.

In Europe, there has been much heated and passionate debate in recent times which has culminated in the new EU Copyright Directive, recently approved by the EU Council and, therefore, now ready to be implemented locally in Member States. Article 17 of the Directive amends the previous “Safe Harbour” provisions (contained in the EU Electronic Commerce Directive in 2000) and, broadly speaking, requires content-sharing services to have licences for copyrighted material with “fair remuneration” for rights holders. It also makes platforms liable for content made by its users.

Whilst there is no similar change in prospect in the USA regarding “Safe Harbour” legislation, the Music Modernisation Act 2018 has brought about an extensive overhaul of music copyright and creates a number of new licensing and royalty rules for the digital era. That’s not to say that it’ll all be plain sailing from now on. Recently, Spotify and Amazon have officially challenged a Copyright Royalty Board ruling in the USA that set royalty rates for songwriters there, for on-demand subscription streaming and other mechanical uses, that would rise by 44% over the next five years. Looking at the economics of Spotify’s business, it’s perhaps understandable that they’ve taken this action, but it has been met with howls of protest by rights holders and their representatives, the National Music Publishers Association, for instance, calling it a “shameful” move which equates to “suing songwriters”.

It’s also clear that accurate and swift identification of musical assets are pre-requisites for generating revenue in a fast-moving transactional market.

Furthermore, although the legislative change in Europe has been hailed as a major breakthrough, only time will tell the extent to which it closes the Value Gap. Nevertheless, it is clear that legislation has a central part to play in creating an environment where the Value Gap can be closed, but it cannot be the only instigator of change.

Content management in the digital era has been inadequate and contradictory and, so far, lacking in a clear and coordinated strategy. Delayed awareness and reaction to the changes being brought about by digital content distribution have also contributed to a rights licensing landscape that is extremely complex.

It’s also clear that accurate and swift identification of musical assets are pre-requisites for generating revenue in a fast-moving transactional market. The challenge isn’t based on lack of suitable technology, but in the fact that the relevant data doesn’t all sit in one place. This is a consequence of the fragmented way in which the music industry has traditionally worked, the changing aspects of copyright ownership and the fragmented ownership of songs. As a result, the industry is in the throes of a significant transition. It will inevitably take time, but that may not be a bad thing in the long run as a lot of the data problems being uncovered relate to things that have been taken for granted in the past. Dealing with them in a systematic way now should result in a far more robust data set.

Does this upturn in revenues and investment percolate down through the system to produce an adequate reward for creators? It would seem not yet.

Of course, commerce also continues to play its part. The IFPI Global Music Report 2019 informs us that, in 2018, the global music market grew by 9.7% and that it was the fourth consecutive year of global growth. It was also “the highest rate of growth since IFPI began tracking the market in 1977”. Additionally, the Report states that “fuelled by the continued investment from record companies, the global story is one of dynamic, diverse markets evolving rapidly and finding routes to growth. Within the top 10, some of the fastest growing markets are in Asia and Latin America (South Korea, Brazil) with Asia becoming the second largest region for physical and digital music combined for the first time”.

From a music publishing perspective, there also seems to be a rebound in fortunes which has been reflected by a number of significant music publishing business acquisitions in the last couple of years. The rapid rise of streaming and the effective push by streaming companies to increase their user base may well have acted as drivers for this activity. In any event, it would seem unlikely that such investment would be occurring if the investors didn’t believe in the business proposition.

Does this upturn in revenues and investment percolate down through the system to produce an adequate reward for creators? It would seem not yet.

At that moment, whenever it occurs, the “Value Gap” debate should give way to a much more progressive environment.

It’s clear that accurate and swift identification of musical assets are pre-requisites for generating revenue in a fast-moving transactional market. The challenge isn’t based on lack of suitable technology, but in the fact that the relevant data doesn’t all sit in one place. This is a consequence of the fragmented way in which the music industry has traditionally worked, the changing aspects of copyright ownership and the fragmented ownership of songs. As a result, the industry is in the throes of a significant transition. It will inevitably take time but that may not be a bad thing in the long run as a lot of the data problems being uncovered relate to things that have been taken for granted in the past, and they’re now having to be dealt with in a systematic way in order to solve them.

Those who are still looking backwards will simply be facing the wrong way.

What’s next?

The fact that digital technologies have revolutionised the distribution of music is beyond doubt. Establishing what the “Value Gap” really is, especially when compared against benchmarks set in the old world of physical product, is much tougher. Commerce will ultimately drive its own solution, as it always does, but not without the continued help of legislation, better data management, more effective licensing models and, above all, collaboration between all the stakeholders, including creators, artists and other rights holders. At that moment, whenever it occurs, the “Value Gap” debate should give way to a much more progressive environment. Those who are still looking backwards will simply be facing the wrong way.

Paul Kempton, Managing Director, Footprint Music Ltd

T: +44 (0)1344 887880

paul.kempton@footprintmusic.com

Paul is Founder and Managing Director of the Footprint Music Ltd, a specialist rights and licensing consultancy celebrating its 25th anniversary this year. The consultancy is focused solely on music copyright and associated rights in the media and entertainment industries. Paul has advised both national and international television broadcasters, digital platforms and content makers and has appeared as an expert witness or filed expert testimony in a number of international court cases, tribunals and mediations. He is also a member of the International Association of Entertainment Lawyers and was co-editor of their 2018 yearbook “Finding the Value in the Gap”.