Understand Your Rights. Solve Your Legal Problems

A new investigation by South Korea's Truth and Reconciliation Commission has exposed the shocking scale of malpractice in the country's postwar adoption program.

Fabricated birth records, false claims of child abandonment, and poor vetting of adoptive parents were rampant during South Korea’s massive international adoption efforts.

Over 200,000 children were sent abroad between the 1950s and the 1990s, many under deceptive and coercive circumstances. The findings highlight the deep-rooted flaws of the system that affected adoptees worldwide.

In the aftermath of the Korean War and World War II, South Korea faced immense poverty and social instability. As a result, private adoption agencies played a dominant role in sending children overseas, often motivated by the financial support they received from adoptive parents.

This reliance on donations led to a system where speed and numbers were prioritized over the well-being of the children. The government largely left the process unchecked, fueling a cycle of misconduct that went unaddressed for decades.

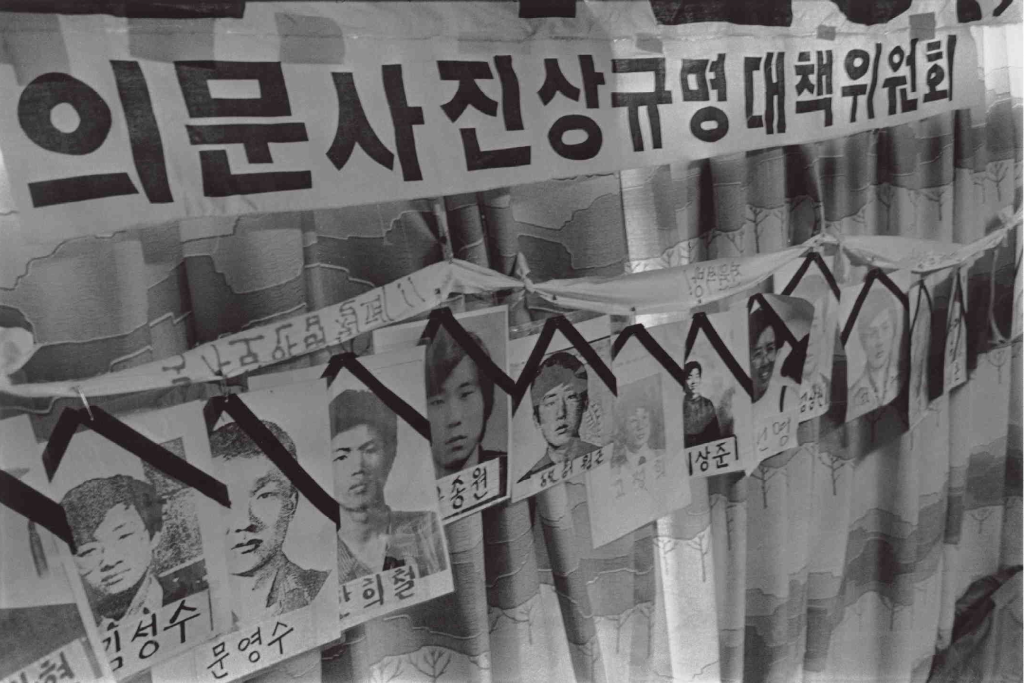

According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, falsified records were a key element of the adoption process. Many children’s identities were deliberately altered, and false reports were often filed claiming that children had been abandoned by their birth parents.

In numerous cases, adoption agencies neglected to obtain proper consent from biological parents, allowing children to be taken under fraudulent circumstances.

One alarming example in the report describes a mother who was pressured to sign adoption papers immediately after childbirth, with no verification of her identity or her relationship to the child.

These manipulative practices became standard in the adoption system, which often placed the financial interests of the agencies above the rights of the children and their families.

The investigation focused on 100 of 367 cases filed by adoptees seeking answers about their origins. Of these, 56 were found to be victims of government negligence, violating their constitutional rights.

Many adoptees now living abroad have spent years trying to trace their roots, but the falsified records have made this process nearly impossible. For some, the emotional toll is compounded by a sense of loss, as they are unable to reclaim their true identities or understand the circumstances of their adoption.

Despite these findings, some adoptees have not been recognized as victims, primarily due to insufficient documentation. This has led to further frustration, with many feeling that their struggles to reconnect with their families are being ignored.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called on the South Korean government to issue an official apology, conduct a survey on adoptees' citizenship statuses, and create reparative measures for victims whose identities were falsified.

The findings are a significant step forward, but many adoptees, like Han Boon-young—raised in Denmark—express dissatisfaction with the limited scope of the investigation.

Han, who was not recognized as a victim due to lack of documentation, stresses the need for greater acknowledgment of all affected adoptees.

While recent changes to South Korea’s adoption laws have sought to reduce overseas adoptions and address past issues, the scars left by years of systemic malpractice remain.

Many in the adoptee community feel that the government’s response falls short of true justice.

Since the 2010s, South Korea has made efforts to reform its adoption laws, aiming to reduce the number of children sent overseas and improve oversight of the adoption process.

Despite this, the legacy of the adoption scandal lingers, with many adoptees still fighting for recognition and justice. The findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission have sparked a necessary dialogue about the past and its ongoing impact on those affected by forced adoptions.

Though the adoption system has evolved, the road to full resolution remains long, and the emotional wounds of adoptees who were deceived or coerced will not easily heal.