Understand Your Rights. Solve Your Legal Problems

At the time of his death in 2025, Val Kilmer left behind not only a legacy of iconic performances but also an estate valued between $10 million and $25 million, according to Finance Monthly. Now, questions emerge over who controls his voice, image, and the royalties tied to his enduring career. This article delves into the legal and personal landscape shaping the future of Kilmer’s posthumous legacy.

Val Kilmer, the enigmatic actor whose screen presence could shift from intense to poetic in a heartbeat, passed away peacefully in Los Angeles at the age of 65. His daughter, Mercedes, confirmed that pneumonia was the cause. Years earlier, Kilmer had faced a grueling battle with throat cancer—a struggle that altered his voice but never dulled his creative fire. Despite the challenges, he continued to paint, write, and perform until the very end. Kilmer leaves behind his children, Mercedes and Jack, both actors following in their father's footsteps, and his brothers, Mark and Wesley.

Kilmer’s death is not just a moment for mourning; it's a moment for legal, cultural, and technological reckoning. For a figure so embedded in the fabric of Hollywood, what he left behind isn't limited to movie rights and royalties. It includes digital assets, likeness rights, intellectual property, and the enduring question of who controls a public persona when the person is no longer present to shape it.

This isn’t a new concern, but it is one that has become far more complicated in the 21st century. In Kilmer’s case, his legacy is multi-dimensional. He wasn’t just an actor. He was a writer, painter, performer, and thinker. His estate, therefore, isn’t just financial. It’s creative, cultural, and increasingly, digital.

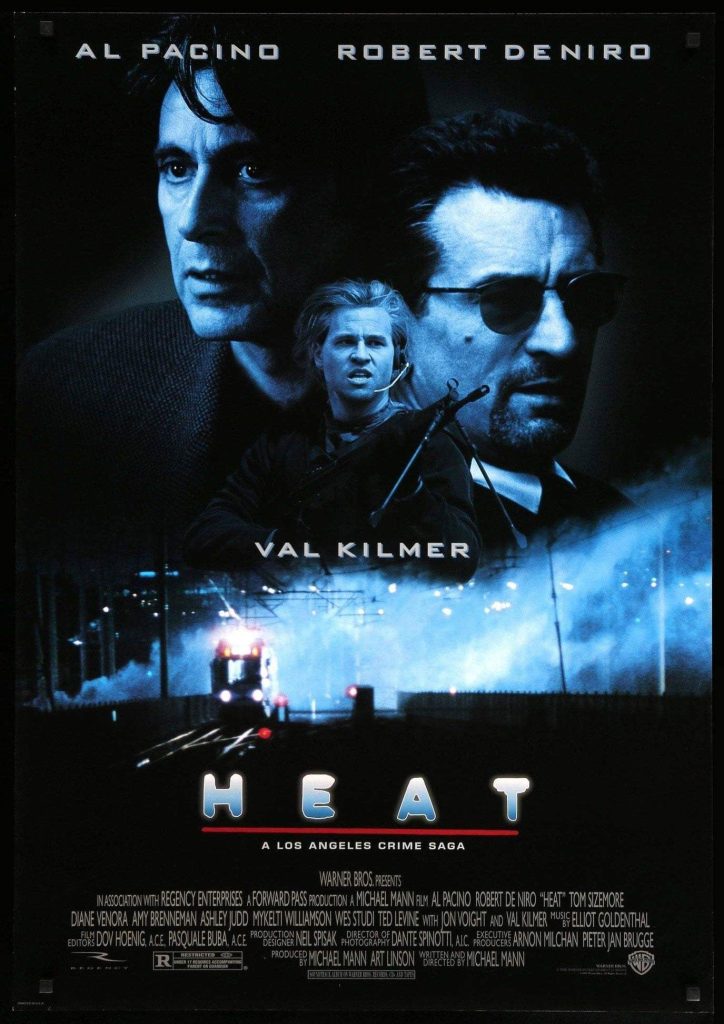

Val Kilmer appeared in Michael Mann’s 1995 crime drama Heat, alongside Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, portraying the fiercely loyal and emotionally complex thief Chris Shiherlis.

When someone passes away, their estate—the total of all they owned and created—needs to be managed. For most people, that includes bank accounts, property, and possessions. But for public figures, it also involves creative works, public likenesses, and sometimes even biometric data like voice recordings and facial scans.

Wills and trusts are the tools used to manage that transition. A will is a legal document that outlines the deceased’s wishes but must go through a public legal process known as probate. Probate can take months, even years, and opens up an estate to public scrutiny. In contrast, a living trust is a private, more flexible arrangement that allows for a smoother, faster transition of assets (What Happens If You Don’t Update Your Estate Plan).

Some celebrities choose irrevocable trusts, which once established, can’t be changed. These are designed to shield assets from legal disputes, estate taxes, or misuse by future heirs. While irrevocable trusts are harder to amend, they offer more protection—a valuable feature when you’re managing decades worth of intellectual property, royalties, and creative assets. Some estates even explore dynasty trusts to maintain control over generations.

Incorporating a trust into an estate plan can offer significant benefits, including the avoidance of probate and enhanced control over asset distribution. Danelle Harrington, a partner at Warner Norcross + Judd, emphasizes the importance of such planning, noting that "estate planning is crucial to avoid difficulties in financial and healthcare management if one becomes disabled."

By establishing a trust, individuals can ensure that their assets are managed and distributed according to their wishes, providing clarity and security for their beneficiaries.

Kilmer’s case is emblematic of a bigger trend: the need to account for digital assets in estate planning. We now live our lives online. Our art, writing, notes, conversations, photos, and videos exist in cloud drives, emails, and apps. Many creators have hundreds, even thousands, of files stored in digital vaults. Some of those are finished works, others unfinished projects that still hold deep personal and artistic value.

That digital presence is part of an estate. And it needs to be treated as such. Naming a digital executor—someone legally empowered to access and manage digital files—has become a key part of modern estate plans. Without it, family members may face legal battles just to retrieve passwords, access drives, or recover creative materials.

Perhaps the most profound illustration of the modern legacy dilemma came when Val Kilmer's voice was digitally recreated for his role in Top Gun: Maverick. Using prior recordings and complex sound modeling, sound engineers were able to rebuild his unique tone and cadence. The result was respectful and moving. But it opened a door to an enormous question: Should we be recreating voices, faces, and personalities after someone dies? (Paramount Pictures Sued Over Top Gun: Maverick)

California's laws provide some clarity. In that state, rights to one's name, image, and voice extend for 70 years after death. That means Kilmer's family, or whoever controls his estate, has the exclusive right to determine how his voice and likeness are used going forward. Whether that’s approving a film cameo, a commercial, or a holographic concert, it’s their decision.

But this responsibility is massive. It's not just about protecting the estate’s value. It's about protecting the integrity of an artist’s work and legacy.

Intellectual property (IP) is the cornerstone of a creative estate. Copyrights, trademarks, and publicity rights can generate income for decades. In the U.S., copyright typically lasts for 70 years after the creator’s death. That includes books, films, photographs, songs, scripts, paintings, and other original works (Understanding IP Rights for the Film Industry).

If Kilmer had unpublished poetry, artwork, or writings, those works are now part of his estate. They can be kept private, published posthumously, or licensed for adaptations. The decisions around those choices rest with whoever controls the estate. Without a clear directive, these decisions can become legal battlegrounds or get bogged down in family disagreements.

With the rise of AI-generated content, even posthumous art has grown controversial. Artists like Celine Dion have spoken out about having their voices used without consent. This illustrates the urgent need for robust legal frameworks to protect both living and deceased creators.

Kilmer’s digitally reconstructed voice in Top Gun: Maverick was widely praised. But imagine a different use: his voice selling insurance, or narrating a political ad. Who decides if that’s okay? Who protects against his image being used in ways that conflict with his beliefs?

Robin Williams, for example, took proactive steps by legally preventing the use of his image and voice for 25 years after his death. That kind of foresight is becoming increasingly important in an era when AI can recreate a face or voice with eerie accuracy.

The legal tools exist, but the ethical lines are still blurry. It’s one thing for a family to preserve a legacy. It’s another to exploit it. Where that line is drawn varies by family, culture, and individual philosophy.

We’ve seen what happens when an estate is mishandled. Prince died without a will. Years later, his estate remained locked in disputes, his music unreleased or mismanaged. Chadwick Boseman's wife had to go through an arduous probate process just to access his accounts. Whitney Houston’s posthumous hologram tour was deeply polarizing.

In a recent high-profile dispute, Limp Bizkit filed a $200 million lawsuit over unpaid royalties, highlighting how unresolved rights and poorly managed contracts can erupt into long legal battles.

Even the order of death can lead to complications. Gene Hackman’s estate may face challenges depending on which spouse legally died first—a grim but important detail in estate law.

When an estate goes off the rails, it’s not just money that gets lost. It’s memory, meaning, and creative continuity.

If you’re a creator of any kind—a writer, filmmaker, designer, musician, or even just someone with a meaningful digital footprint—you need a plan. It doesn't matter whether you’re a household name or not. If what you've created has meaning to you or potential value to others, you owe it to yourself to think about its future.

Start with a will. Better yet, build an estate plan that includes a trust. Name a digital executor. Make a list of your intellectual property and where it’s stored. Be clear about how you want your name, image, and work to be treated. And revisit your plan regularly as life evolves (Protect Your Legacy With Estate Planning).

These steps aren't just legal housekeeping. They're part of authorship. They're part of storytelling. You're deciding how your story continues after you're gone.

We don’t yet know everything that Val Kilmer left behind. Perhaps there are paintings, short films, journals, or screenplays still waiting to be discovered. If properly cared for, they could enrich our understanding of his artistry for years to come. If neglected, they could disappear forever.

Handled right, Kilmer’s estate could inspire future generations. Mishandled, it could become another cautionary tale.

Kilmer once wrote, "I don't believe in death. I see it as a departure on another journey."

That journey continues now—in pixels and paint, in voice and vision, in every life he touched and in every work he left behind.

🧩 Final Thought: You Don’t Have to Be a Star to Leave a Legacy

Val Kilmer’s story reminds us that we’re more than the roles we play. Whether you’re a household name or a quiet creative working late into the night, your voice, your ideas, and your work deserve to be protected.

Take the time to write your ending — or better yet, make sure someone you trust can do it for you when the time comes.

Who manages Val Kilmer’s estate?

No public announcement yet. It’s likely a family member or someone named in his will or trust.

Can AI recreate Val Kilmer’s voice now that he’s passed?

Not without approval. His voice is protected by California’s publicity laws.

What happens when a celebrity dies without a will?

The court decides who inherits. It can be slow, expensive, and lead to conflict.

Is estate planning just for the wealthy?

No. If you create anything of value or care what happens to your story, it’s worth planning.